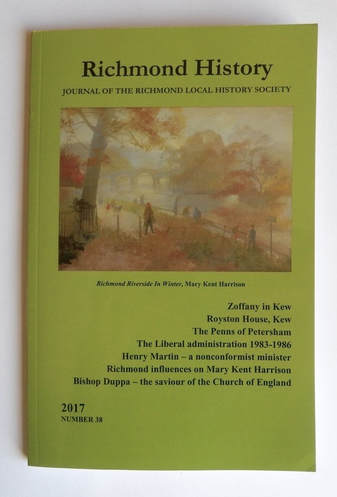

In 2016 I was asked by the editor of Richmond History to write an article about aspects of my mother's time growing up in Richmond, Surrey in the 1930's and 1940's. The article is reproduced below with the kind permission of the editor of Richmond History. The book is available to purchase from www.richmondhistory.org.uk

The artist Mary Kent Harrison (1915–83):

a memoir of her life in Richmond

STEPHEN HOWARD HARRISON

My mother was very fond of Richmond, which shows in the warmth and depth of the paintings that she produced there and which also give a valuable glimpse into life in Richmond at the time. She spent her formative years in the town until the end of the Second World War. Soon after, she moved on with her own growing family to Cambridge and then to Wimbledon and eventually to Lancashire where, in stark contrast to Richmond, home was a remote farmhouse in an equally beautiful though different kind of a place.

I was born after my mother left Richmond, but she often returned there and I remember many walks along the river and also picnics in Richmond Park with her and my siblings. The beauty of the place resonates with me too.

It was in the early 1920s that my grandfather, Howard Marryat, a relative of Captain Frederick Marryat RN (the author of many well-known children's books), acquired the wonderfully positioned house on The Terrace, Richmond Hill. Earlier, Howard and his wife Maude lived in Chiswick, where my mother was born in a house called Thames Dean. She was born in December 1915, when Howard was 43 and Maude was 46.

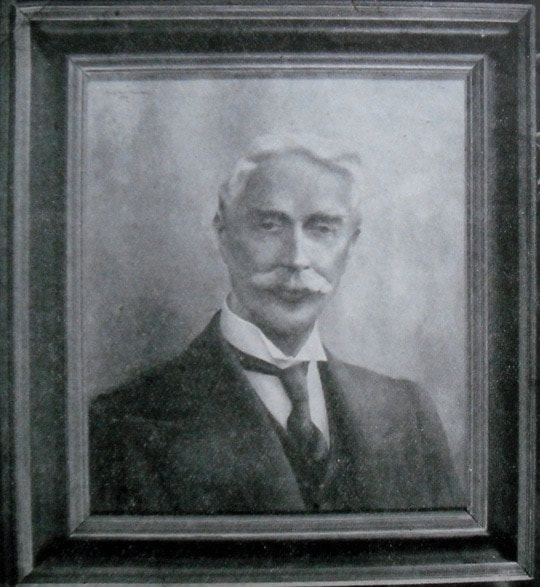

Howard Marryat was a successful and well-liked businessman. His friends affectionately called him HM and he had a great capacity for friendship. He worked fastidiously hard, creating what eventually became an electrical engineering company specialising in the design, manufacture and installation of lifts in buildings all over the world. Amongst many notable achievements his company, Marryat & Scott, was responsible for the first electrical motor coupled to a printing press. He was a pioneer in the field of electrical engineering and wrote and lectured on the subject. His offices were in Hatton Gardens. He took the Southern train every day from Richmond to Waterloo and then walked to his offices, often being accompanied to the station by his sons and daughters. It was a fairly easy commute, and at that time Richmond was still quite separate from London.

Richmond Bridge 1940s (Courtesy of the author)

Richmond Bridge 1940s (Courtesy of the author)

My mother was devoutly religious, and it is likely that the Marryats attended church regularly, probably at St Matthias on Richmond Hill. Her first romantic attachment was to a local curate but the relationship ended because of his insistence that Mary should abandon any artistic career. Her father sought to help heal the emotional wounds, by sending her off on a tour of the Middle East in 1936. A few very good portrait drawings of the people she encountered there survive.

Maude was very supportive of her husband's career, and she took a keen interest in the welfare of the firm's employees. She arranged Christmas parties in the house for Howardʼs staff and their families. She also supported the staff on a personal level in times of need or distress. Their home was certainly large enough for such entertaining. There were the children to look after too, and that fact would have inevitably determined a great deal of the daily routine and opportunities available.

I think that my grandparents were, like so many, attracted to Richmond by its beauty. The fact that it had a semi-rural feel must have appealed, hence the decision to purchase the house on The Terrace with its enviable views looking west down the Terrace Field and over the Thames and Glover Island as the river gently curves around into the distance. The island was a useful focal point in the compositions my mother painted of the view.

My brother Malcolm remembers wonderful sunsets from the first- floor ballroom of the house. Our mother had her studio area sometimes in a room at the back of the house overlooking the garden and from which Malcolm remembers her being able to watch over him in the garden. It was from the balcony windows of the ballroom that she painted many fine views of the river, the best- known being Victory Day, Richmond (1945). The painting appeared in George Orwell's book The English People (Collins, 1947) as well as on the cover of the Richmond Local History Society’s book Richmond at War 1939–1945.

They had at least one dog – a greyhound called Flash – who required frequent walks. According to Malcolm, Flash used to make an awful lot of noise in the streets raiding the dustbins for food and chasing the deer in Richmond Park.

My mother made several paintings of the Park of which Nut Gatherers in Richmond Park is particularly evocative. She also produced many paintings of the river and Richmond Bridge, in which she showed walkers enjoying the beauty of the place.

As a young man, Howard was a keen swimmer and cyclist. He once walked from Richmond to Exeter and back, accompanied by his dog. Richmond, it seems, provided the right environment where outdoor pursuits could be enjoyed, yet all the benefits of the capital city were within easy reach. Her love of walking was something that my mother inherited from Howard: I remember many long walks with her later on in her life in the Yorkshire Dales.

As a young man, Howard was a keen swimmer and cyclist. He once walked from Richmond to Exeter and back, accompanied by his dog. Richmond, it seems, provided the right environment where outdoor pursuits could be enjoyed, yet all the benefits of the capital city were within easy reach. Her love of walking was something that my mother inherited from Howard: I remember many long walks with her later on in her life in the Yorkshire Dales.

Thanks to Howard's business acumen the family were able to live relatively comfortably, at least in the period before the Second World War. My cousin Adrian remembers a staff room in the basement, and also a huge Aga in the kitchen. There was a live-in maid called Beatrice, and a chauffeur and gardener who were not in residence. He remembers Maude being brought breakfast to her bedroom by Beatrice. Adrian recalls that the kitchen was out of bounds to him and Malcolm. The time Malcolm ate the whole week’s wartime ration of butter in one go may have had something to do with the implementation of this rule.

Howard was very definitely a self-made man. After receiving his technical training at the Finsbury Technical College, he set up his business when only twenty years old and remained at the helm for no less than 53 years. Undoubtedly, he set the tone of the house. I know that he and his daughter Mary were very close, perhaps enjoying a closer relationship than the relationship between Howard and his sons John and Robert. There may have been some unease as a result of the pressure that he put on his son John to join the family business and follow in his footsteps. The closeness between my grandfather and his daughter may have intensified due to the tragic early death, from Hodgekins disease, of Howardʼs beloved eldest daughter, Cecily, with whom my mother had formed a close relationship. So, there was certainly great sadness and a sense of bereavement added into the emotional mix as Mary approached adulthood. That my parents gave the name Cecily to their first daughter was perhaps a sign of this.

I envy Malcolm's ability to actually remember Howard and understand his personality. Malcolm found him likeable and recalls his commanding height and his distinguished white moustache. Howardʼs face was enlivened by intense blue eyes.

The influence of Howard on my mother was the most important factor of my mother's time at Richmond. For, apart from his demanding business life, he was a man of a great many other interests. They were not in themselves as important as the manner in which he pursued them and the intellectual vigour and discipline which he brought to them. Of particular interest was his collection of fine antique watches. They were described as ‘the finest collection of watches in private hands in this country’. Not only did Howard collect watches, he also wrote about them. In his book, Watches – Henlein to Tompion (1938) one cannot be other than enthralled by Howardʼs depth of specialist or encyclopaedic knowledge. Perhaps in horology Howard found a perfect mixture of fine art, engineering and craftsmanship which reflected his own temperament most appropriately. Howard was also a keen photographer and there was a darkroom built in the garden. He took all the photographs of the watches which appear in the book. The disciplined, fastidious and serious nature with which Howard wrote, learnt about and described the items in his collections found echoes later in the paintings by my mother where similar qualities are clearly evident.

Howard was very definitely a self-made man. After receiving his technical training at the Finsbury Technical College, he set up his business when only twenty years old and remained at the helm for no less than 53 years. Undoubtedly, he set the tone of the house. I know that he and his daughter Mary were very close, perhaps enjoying a closer relationship than the relationship between Howard and his sons John and Robert. There may have been some unease as a result of the pressure that he put on his son John to join the family business and follow in his footsteps. The closeness between my grandfather and his daughter may have intensified due to the tragic early death, from Hodgekins disease, of Howardʼs beloved eldest daughter, Cecily, with whom my mother had formed a close relationship. So, there was certainly great sadness and a sense of bereavement added into the emotional mix as Mary approached adulthood. That my parents gave the name Cecily to their first daughter was perhaps a sign of this.

I envy Malcolm's ability to actually remember Howard and understand his personality. Malcolm found him likeable and recalls his commanding height and his distinguished white moustache. Howardʼs face was enlivened by intense blue eyes.

The influence of Howard on my mother was the most important factor of my mother's time at Richmond. For, apart from his demanding business life, he was a man of a great many other interests. They were not in themselves as important as the manner in which he pursued them and the intellectual vigour and discipline which he brought to them. Of particular interest was his collection of fine antique watches. They were described as ‘the finest collection of watches in private hands in this country’. Not only did Howard collect watches, he also wrote about them. In his book, Watches – Henlein to Tompion (1938) one cannot be other than enthralled by Howardʼs depth of specialist or encyclopaedic knowledge. Perhaps in horology Howard found a perfect mixture of fine art, engineering and craftsmanship which reflected his own temperament most appropriately. Howard was also a keen photographer and there was a darkroom built in the garden. He took all the photographs of the watches which appear in the book. The disciplined, fastidious and serious nature with which Howard wrote, learnt about and described the items in his collections found echoes later in the paintings by my mother where similar qualities are clearly evident.

Grandfather’s house was no doubt full of valuable and delicate objects. Adrian recalls two suits of armour in the drawing room that were ‘never to be touched’. Such reverence for the collections would have tempered the tone of the house for its occupants, especially one with small children. Adrian also recalls further that Howard had a very large telescope on the landing that must have been particularly vulnerable. It was no ordinary telescope. It was one of five telescopes made by William Herschel (1738–1822). Howard Marryat bought it in 1927, but presented it to Robert Whipple in1944, after Whipple's gift of 2000 scientific instruments and books to the University of Cambridge. It is currently on display at the Whipple Museum of the History of Science in Cambridge. I can imagine how panic-stricken Adrian must have been when, after playing with it, a part came off and the boy was called to see Howard in his study the next day to 'discuss' the matter!

I think therefore that the house was usually fairly sombre. Indeed, Adrian recalls it as being strict. Everyone was expected to dress formally for the evening meal and they were served by Beatrice, who went around the long dining room table, starting with Maude and finishing with Howard. There would have been fun and games but only at specific times and in the right place, and such humorous moments would have complemented other times of intense study and reverence. There was a handsome hand-painted rocking horse in the ballroom, on the first floor, that both Malcolm and Adrian vividly recall riding. It was set up by the window, and the view over the Thames and beyond might have inspired them as they galloped over distant imagined lands. The rocking horse was also ridden by my other siblings and me. Malcolm remembers riding a tricycle around what seemed to him at the time an enormous dining table under which Adrian recalls sheltering during air raids – and of course there was the large garden to make use of when there were tea parties and also fancy dress parties.

My mother was sent to board at the delightfully named Twizzletwig School for Girls in Hindhead, where the headmistress was her godmother Auntie Bell. She must have come home to Richmond for the holidays to find her father keen to show her his latest acquisition of fine art or craft or ancient artefact. It would surely have been then that Mary would have been drawn to fine art, which ultimately led to the Slade School of Art and the Royal Academy where, with a discipline and fastidious attention to detail and structure inherited from her father, along with an aptitude for sheer hard work, she learnt to hone her skills. When I look at her art school drawings in anatomical studies, perspective and calligraphy, I see the same extraordinary spirit of learning, focus and serious inquiry that I sense when I read her father's books.

I think therefore that the house was usually fairly sombre. Indeed, Adrian recalls it as being strict. Everyone was expected to dress formally for the evening meal and they were served by Beatrice, who went around the long dining room table, starting with Maude and finishing with Howard. There would have been fun and games but only at specific times and in the right place, and such humorous moments would have complemented other times of intense study and reverence. There was a handsome hand-painted rocking horse in the ballroom, on the first floor, that both Malcolm and Adrian vividly recall riding. It was set up by the window, and the view over the Thames and beyond might have inspired them as they galloped over distant imagined lands. The rocking horse was also ridden by my other siblings and me. Malcolm remembers riding a tricycle around what seemed to him at the time an enormous dining table under which Adrian recalls sheltering during air raids – and of course there was the large garden to make use of when there were tea parties and also fancy dress parties.

My mother was sent to board at the delightfully named Twizzletwig School for Girls in Hindhead, where the headmistress was her godmother Auntie Bell. She must have come home to Richmond for the holidays to find her father keen to show her his latest acquisition of fine art or craft or ancient artefact. It would surely have been then that Mary would have been drawn to fine art, which ultimately led to the Slade School of Art and the Royal Academy where, with a discipline and fastidious attention to detail and structure inherited from her father, along with an aptitude for sheer hard work, she learnt to hone her skills. When I look at her art school drawings in anatomical studies, perspective and calligraphy, I see the same extraordinary spirit of learning, focus and serious inquiry that I sense when I read her father's books.

My mother learnt much from him, but she was to add something that perhaps went beyond what Howard achieved. His strength lay in the cataloguing and explanation of what was made by others in the field of fine art. Her fortitude and single mindedness enabled her to actually make works of art herself – works that possess quite extraordinary subtlety, discipline and complexity, and convey to others her own personal sensitivity and the manifestation of beauty that she chose to see, even at times of great adversity during which she remained incorruptible. She saw this beauty in the places around her that she came to love such as Richmond, and the delicate flowers that she focused on, and also in the people in her world as her life unfolded.

Not only did my mother grow up in Richmond – she also married George Kent Harrison, a Canadian, just before the outbreak of war in 1939, at St Matthias Church, followed by an impressive wedding reception in the garden at The Terrace. After marriage Mary signed her paintings Mary Kent. During the war my father was sent overseas to the Middle East where he was a surgeon in the Royal Army Medical Corps. My mother was employed in Bath by the Admiralty as a cartographer. But, with the arrival of her first son Malcolm, and her husband away overseas, she moved back to The Terrace to live with her parents. In 1940, she had her first one-woman show at Brooke Street Galleries, New Bond Street.

Life now revolved around air raid warnings and, of course, the effects of food rationing. During the summer of 1944 a V1 flying bomb landed not far from the end of the garden. Debris came through the large atrium window and the house was damaged. Remarkably, Malcolm slept through the whole event.

Malcolm also has memories of the shortage of food and in particular the effect of a shortage of Vitamin C, resulting in a family member developing rickets. My mother's 1946 painting The Clinic shows the premises on Upper Richmond Road where parents took their children for health checks.

Howard's business premises in Hatton Garden was badly hit in the Blitz, and a portrait my mother painted of him was lost. By 1944 Howardʼs health was poor. He suffered a fatal heart attack at Waterloo Station on his way to read a paper to the Institute of Electrical Engineers. Maude was overcome with grief and only survived Howard by a year.

My mother exhibited three paintings In Richmond Park, The Terrace, Autumn, and The Terrace, VE Day in the ‘Exhibition of Richmond – Yesterday, Today, Tomorrow’ which took place at the Town Hall in August 1945.

The house on The Terrace was sold soon after the end of war. The family moved to Cambridge and then in 1952 to Wimbledon. There were many family outings to Richmond, and from such excursions I too developed a great fondness for the place. As late as 1975 I accompanied my mother on a sketching trip to the riverside. Clearly it was a place dear to her heart.

In some ways my motherʼs story came full circle back to Richmond. After an extraordinarily productive life as a painter and mother, her funeral took place at St Matthias in 1983. Remarkably, the service was led by the same minister, the Reverend G H M Gray, who had conducted her marriage ceremony.

Further reading

More about Mary Kent Harrison, with examples of many of her paintings, can be found at www.marykentharrison.com

Not only did my mother grow up in Richmond – she also married George Kent Harrison, a Canadian, just before the outbreak of war in 1939, at St Matthias Church, followed by an impressive wedding reception in the garden at The Terrace. After marriage Mary signed her paintings Mary Kent. During the war my father was sent overseas to the Middle East where he was a surgeon in the Royal Army Medical Corps. My mother was employed in Bath by the Admiralty as a cartographer. But, with the arrival of her first son Malcolm, and her husband away overseas, she moved back to The Terrace to live with her parents. In 1940, she had her first one-woman show at Brooke Street Galleries, New Bond Street.

Life now revolved around air raid warnings and, of course, the effects of food rationing. During the summer of 1944 a V1 flying bomb landed not far from the end of the garden. Debris came through the large atrium window and the house was damaged. Remarkably, Malcolm slept through the whole event.

Malcolm also has memories of the shortage of food and in particular the effect of a shortage of Vitamin C, resulting in a family member developing rickets. My mother's 1946 painting The Clinic shows the premises on Upper Richmond Road where parents took their children for health checks.

Howard's business premises in Hatton Garden was badly hit in the Blitz, and a portrait my mother painted of him was lost. By 1944 Howardʼs health was poor. He suffered a fatal heart attack at Waterloo Station on his way to read a paper to the Institute of Electrical Engineers. Maude was overcome with grief and only survived Howard by a year.

My mother exhibited three paintings In Richmond Park, The Terrace, Autumn, and The Terrace, VE Day in the ‘Exhibition of Richmond – Yesterday, Today, Tomorrow’ which took place at the Town Hall in August 1945.

The house on The Terrace was sold soon after the end of war. The family moved to Cambridge and then in 1952 to Wimbledon. There were many family outings to Richmond, and from such excursions I too developed a great fondness for the place. As late as 1975 I accompanied my mother on a sketching trip to the riverside. Clearly it was a place dear to her heart.

In some ways my motherʼs story came full circle back to Richmond. After an extraordinarily productive life as a painter and mother, her funeral took place at St Matthias in 1983. Remarkably, the service was led by the same minister, the Reverend G H M Gray, who had conducted her marriage ceremony.

Further reading

More about Mary Kent Harrison, with examples of many of her paintings, can be found at www.marykentharrison.com